This article was written by Alison F. Takemura and originally published in Canary Media on March 3, 2022.

I have a confession: I worked on a fossil fuel divestment campaign, but I didn’t know how to divest my own money.

I used to avoid my investments like they had gone rank in the fridge. In 2016, an employer opened my first 401(k) account, and for more than a year, I didn’t actually know which companies my new retirement savings were invested in. Did they manufacture weapons? Operate private prisons? Or profit from fossil fuels? The possibility that my money was funding and I was profiting from fossil fuel production really galled me, because I had, for years, lobbied my university, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, to divest from fossil fuel companies. But now that I had my own investments, I didn’t know how to divest them. I waited an embarrassingly long time to figure it out.

But you don’t have to. I’ll guide you through how to divest.

First, though: The movement to divest from fossil fuels has reached heights of popularity I never expected it to. Two of my alma maters have divested — the University of California system and the University of Oxford. Last year, even Harvard, which had resisted for a decade, moved to divest its $41.9 billion endowment, the largest of any single university. In 2018, Ireland became the first country to pledge to dump its investments in coal, oil, peat and gas. The Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis recommends divesting — and so does the pope. In 2020, a group of researchers picked fossil fuel divestment as one of the concrete ways to help tip society toward rapid carbon-neutral transformation. Even Sir David Attenborough — “as close to a secular saint as we’re likely to see,” as one writer put it — advocates that we divest from fossil fuels.

Detangling the process of personal divestment took me a while. But by sharing what I learned, I intend to make it far easier for you.

Three strategies

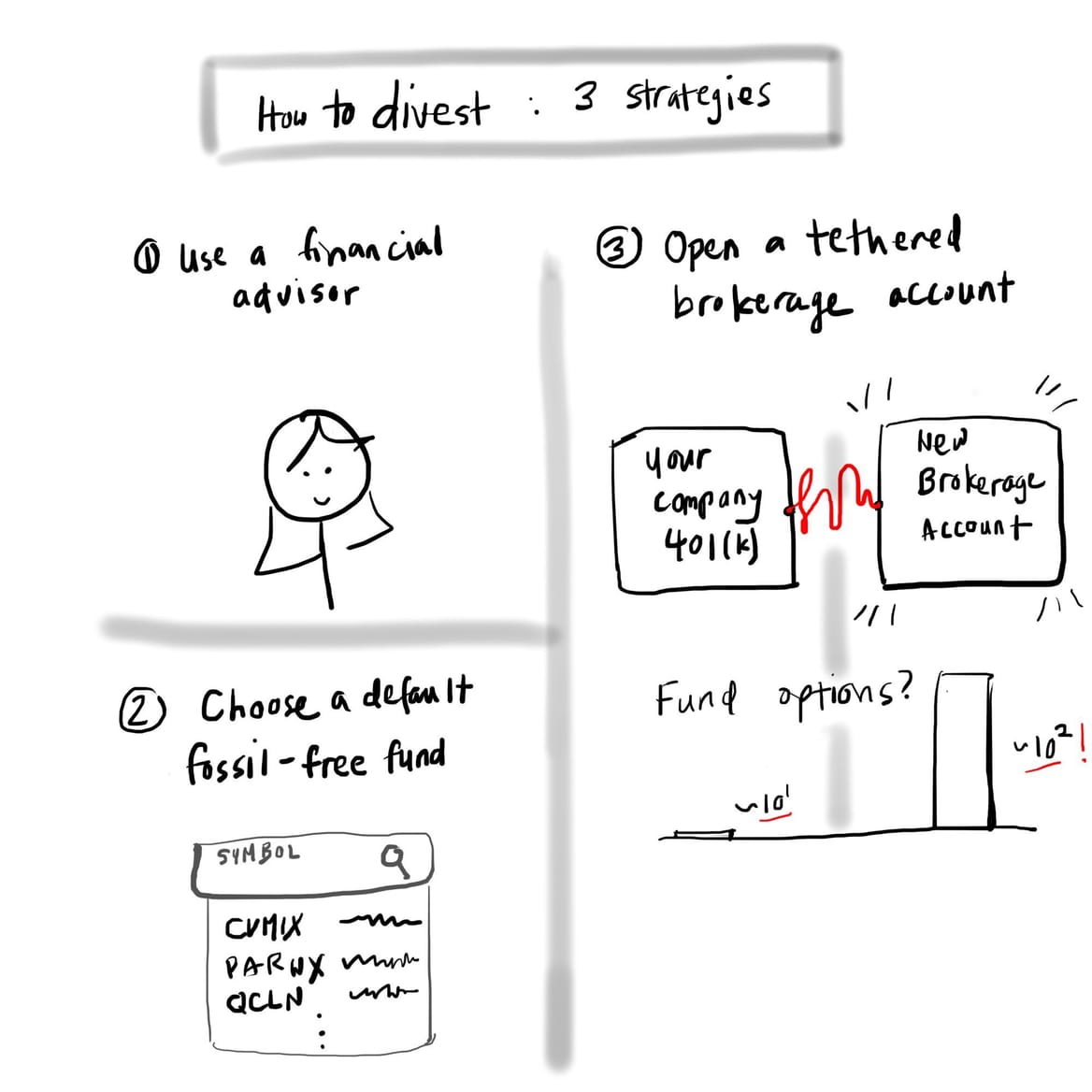

To divest, I offer you, broadly, three strategies.

The first option is to ask your financial adviser to do it for you — or at least help you evaluate your options. You might not know you have a financial adviser; I certainly didn’t when my then-employer MIT opened my retirement account but didn’t tell me how to use it. But financial advisers come with these accounts. You’re entitled to their time, free of (extra) charge. Your account pays for them; they work for you.

The second option: If you’re lucky, your company already offers a fossil-free fund right out of the gate. Select it as your investment, and bada bing, you’re divested.

The third option, which you might not know exists, is to open a new account but one that’s tethered, like an astronaut to a broken shuttle, to the 401(k) (or its nonprofit equivalent, the 403(b)) that your company originally set up. But this new account? It comes with much more freedom to choose where to invest your money.

Here’s a schematic summarizing the strategies:

Breaking free

Let’s consider your initial state. Your 401(k) might be set up to automatically invest in a preselected fund: a bundle of different investments that have a mix of stocks and bonds. What I’ve seen most often is that, by default, this fund is a target-date fund; for example, if you plan to retire in 2050, then the fund might have 2050 in its name. Year by year, the fund will become progressively more conservative, investing in safer things like bonds. But these funds often have little transparency about what they hold and could be hiding petroleum-stained stocks. That’s why using a tethered “brokerage account” is liberating; you get to be the broker and be pickier about what funds you invest in.

Note, though, that these tethered accounts are, unhelpfully, called different things by different financial institutions. For example, at Fidelity, it’s a “BrokerageLink” account, and at Schwab, it’s a “Personal Choice Retirement Account.” But they work the same way.

Something to watch out for: While many employers let you open this tethered brokerage account, not all do. Some think it’s too risky for you to decide where your money goes. Really. When I was on the phone with a Fidelity adviser, that’s what they told me. If you’re in this sorry situation, badger your employer to let you make your own informed choices.

It can take a couple of days for your financial institution to open your tethered brokerage account. But once it’s done, it’s time to move your money. See the illustration of this below to help you visualize. You have your current investments in your 401(k). If you sell those, you now have money that you can use with your new brokerage account to stock up on a fossil-free fund. This is the key to how to divest: sell, get cash, buy.

If you make a fossil-free fund the default for all your future contributions, you’re done. You’ve officially divested from fossil fuel corporations.

Oh, the choices you’ll find!

But which fossil-free fund to choose? With your brokerage account, you’re like a baby chick freshly hatched into a world of financial choice. But the bad news first: Your employer might be limiting what funds you can invest in. Now, the good news: You’re still likely to have access to an order of magnitude more funds through your brokerage account, with a number of them free from fossil fuels.

To help you choose among the funds out there, I recommend using the online tool Fossil Free Funds. Created by the socially responsible investing nonprofit As You Sow, in collaboration with the investment research firm Morningstar, the online tool shows you their top fossil-free picks, like the Parnassus Endeavor Fund (PARWX), the Calvert Emerging Markets Equity I Fund (CVMIX) and the Pax Global Environmental Markets Fund (PGINX).

What does the tool mean by “fossil-free”? It means that a fund does not hold stock in the following:

- The top 200 owners of fossil fuel reserves.

- Coal companies.

- Oil and gas companies, identified by Morningstar as involved in drilling, extraction, production, refining and marketing.

- The 30 largest public-company owners of coal-fired power plants.

- Fossil-fired utilities.

Among the companies that get screened out, you’ll find the usual suspects: BP, ConocoPhillips, ExxonMobil and Royal Dutch Shell.

Here’s a screenshot of what Fossil Free Funds shows you if you click on a particular fund. Note that this fund is fossil-free in all five categories that the tool evaluates.

But funds, being bundles of stocks and bonds, aren’t static. They’re constantly changing their holdings. So As You Sow and Morningstar score funds every quarter, analyzing an eye-popping 9,000-plus funds. Their tool also allows you to see which companies each fund is invested in, how diversified the funds are and what fees they charge (fees nibble into your earnings, a loss that compounds over time). This freely available information means you don’t have to be a Wall Street day trader to compare these funds. You can evaluate them yourself and choose which ones to invest in. With all its data, Fossil Free Funds has made me pleased as a cat in the sun.

Companies with foresight

Now you might be thinking, “I’m psyched!” But are there potential risks? It’s always risky to invest in the stock market. But some companies are going to be riskier than others.

Fossil fuel companies such as ExxonMobil are notorious for their focus on short-term profits to the detriment of people, the environment and stable countries (see Rachel Maddow’s stunning book Blowout: Corrupted Democracy, Rogue State Russia, and the Richest, Most Destructive Industry on Earth). Shortsighted companies rarely make for good long-term investments.

Consider a company that dumps pollutants into a river rather than purchasing a state-of-the-art water filtration system or detoxifying their process upstream, says As You Sow’s CEO Andy Behar. “Think of the legal fees they’d have to spend in lawsuits,” he adds. “Especially for young people thinking about retirement, you want a company that takes the long view and invests in sound judgment.”

Research shows that companies with foresight aren’t bad investments either. Thus far, fossil-free funds tend to do as well or even outperform funds still invested in fossil fuel companies.

Troubleshoot

I’ve laid out a path for you to divest, but you might encounter difficulties. If so, don’t worry; I’ve been there. Here are some things to try:

- If you have trouble navigating your financial institution’s convoluted web interface, remember: Others have probably encountered a similar issue and organizations might have created guidance online. That’s exactly what Yale did. Try searching “how to choose your own fund, brokerage retirement account, [your workplace], [your financial institution]” or a similar variant.

- You can also call your financial institution and ask how to divest on its platform, step-by-step. I’ve called half a dozen times and encourage you to do the same if all else fails.

At the end of the divestment rainbow

Divesting is one approach to a better world.

“If all people invested with their values, then all the capital would go to the people who care about these issues,” says Behar. “It just shifts trillions of dollars toward an economy based on justice and sustainability.”

Sounds good, right? And once you know how to swap investments you loathe for those you love, you can extend this superpower to any issue you care about: deforestation, guns, gender inequality, the prison industrial complex, and so on. The well is deep.

If you start to feel overwhelmed, I want to reassure you: You can do this. Take baby steps. Any action is better than no action. And there is no perfect way to divest; we each only have so much time to navigate the complex ecosystem that is personal finance. No one will judge you for your investments; everyone’s worrying about their own. So pick a fund you feel good enough about, and if you have more time later, you can come back to it and reevaluate. With investments, it’s a good idea to revisit them annually, anyway. (In fact, becoming aware of how to divest may lead you to strategically diversify. You might partially invest in a fund that has fossil fuel holdings, not to profit from a climate-denying business model, but to deliberately exercise its rights as a shareholder to steer companies toward positive change.)

Read the original article here: https://www.canarymedia.com/articles/fossil-fuels/how-to-divest-your-401k-from-fossil-fuels?utm_campaign=canary&utm_medium=email&_hsmi=205674766&_hsenc=p2ANqtz-jmCUMWAKJsuHo2zILyMlWfEkeYm0vNn55lCHZf4OSxeM1HcqGaoFgtgaO0fqA8D9qYwxjDPXjkn-UHySiLjAMMWZS9Q&utm_source=newsletter